This is an updated version of the original gender pay gap article we published in 2021. The findings discussed are drawn from a survey of 501 US workers that we carried out in the same year.

In 2022, female employees in the US earned 82% of what male employees earned for similar work. In other words, for every $1 a man earned, a woman in the same position earned 82 ¢.

In this article, we’ll explore attitudes toward the gender pay gap and how they differ across different age groups, regions, and genders.

How workers view the gender pay gap situation

Resume Genius asked 501 Americans what they thought about the gender pay gap and whether they thought it could be closed in their lifetimes.

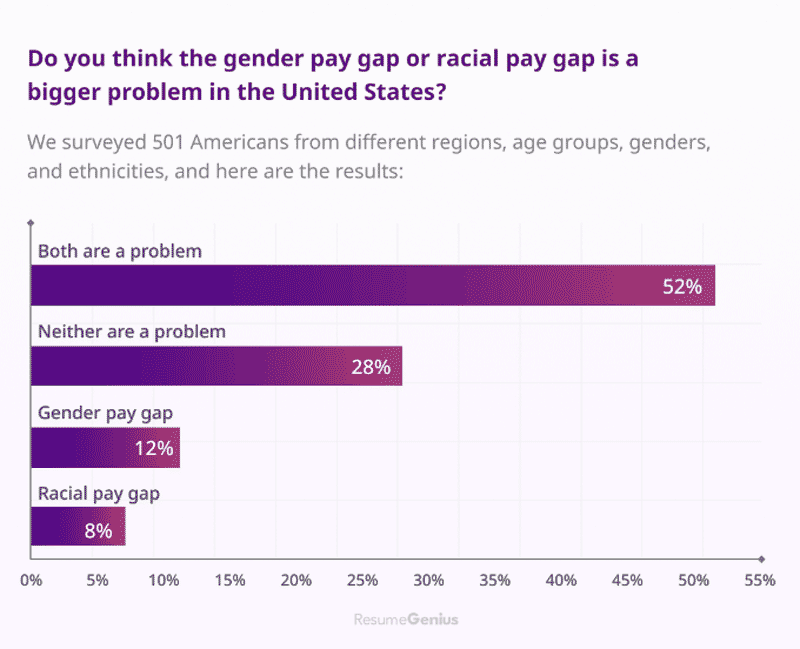

Most people agreed that both the racial pay gap and gender pay gap are substantial problems:

In total, 72% of people acknowledged that the gender pay gap is a problem.

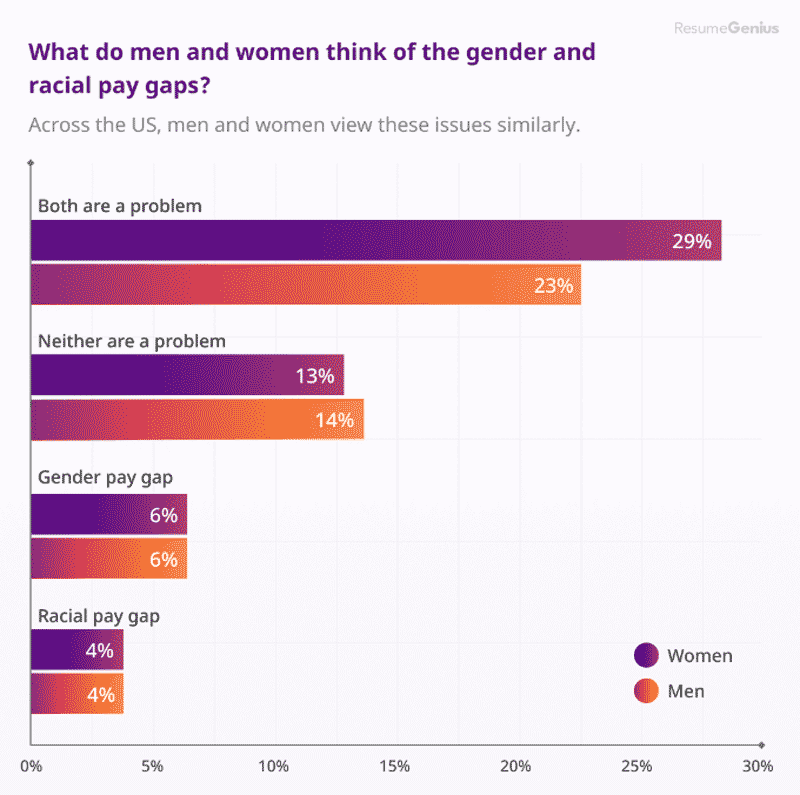

However, a smaller proportion of men than women were concerned about the gender-related issues that women face in the workplace.

For example, in this chart men are more likely than women to say that neither the gender wage gap nor the racial wage gap are problematic:

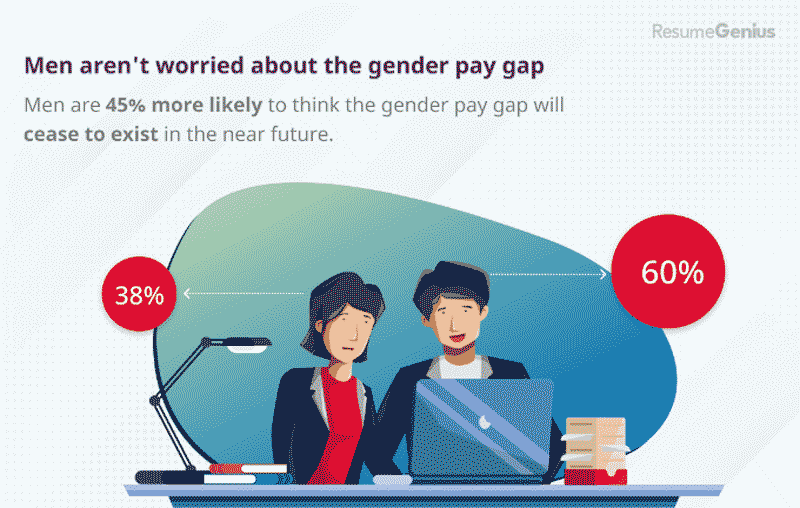

Turning to attitudes about the outlook for the gender pay gap, little more than a third of surveyed women (38%) believed that complete gender pay equality will be achieved in their lifetimes:

Despite the narrower gender pay gap today — women now make 84¢ for every $1 a man earns, compared to 64¢ for every $1 in 1980 — many women felt it was unlikely that wage equality will be achieved in the near-to-mid future.

The data also shows that the majority of male respondents — 60%, almost double the percentage of women — believed the gender pay gap will cease to exist in their lifetimes.

Maternity leave

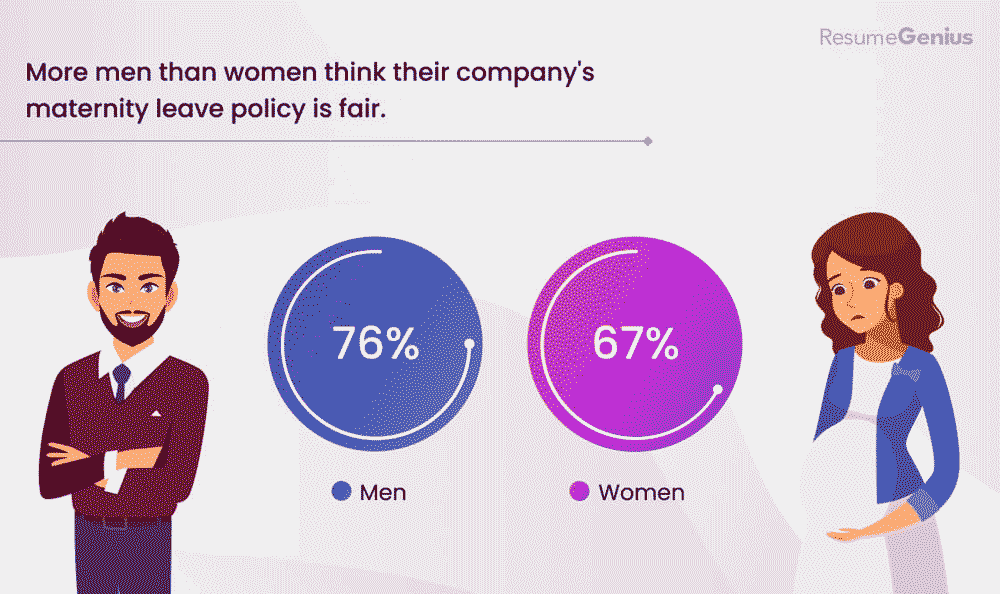

One significant insight from the data was that men and women often have differing views on gender issues in the workplace. Men were less likely than women to consider the gender-related issues women face as important.

For example, men were more likely than women to believe their company’s maternity leave was fair.

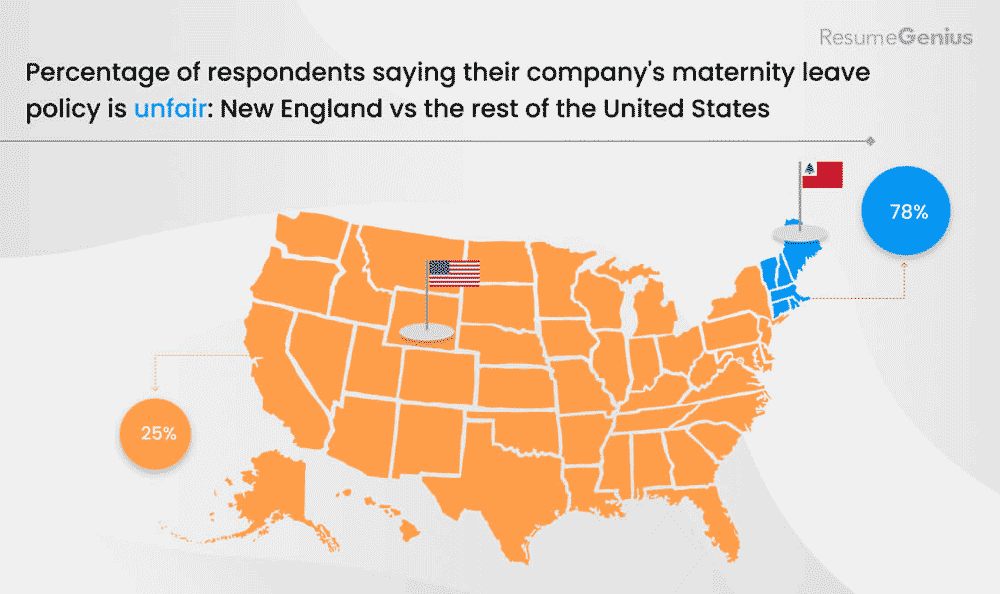

The survey also suggested that attitudes toward maternity leave policies varied considerably in certain regions. For example, a far greater share of respondents in New England said their company’s maternity leave policy was unfair compared to respondents in other US regions.

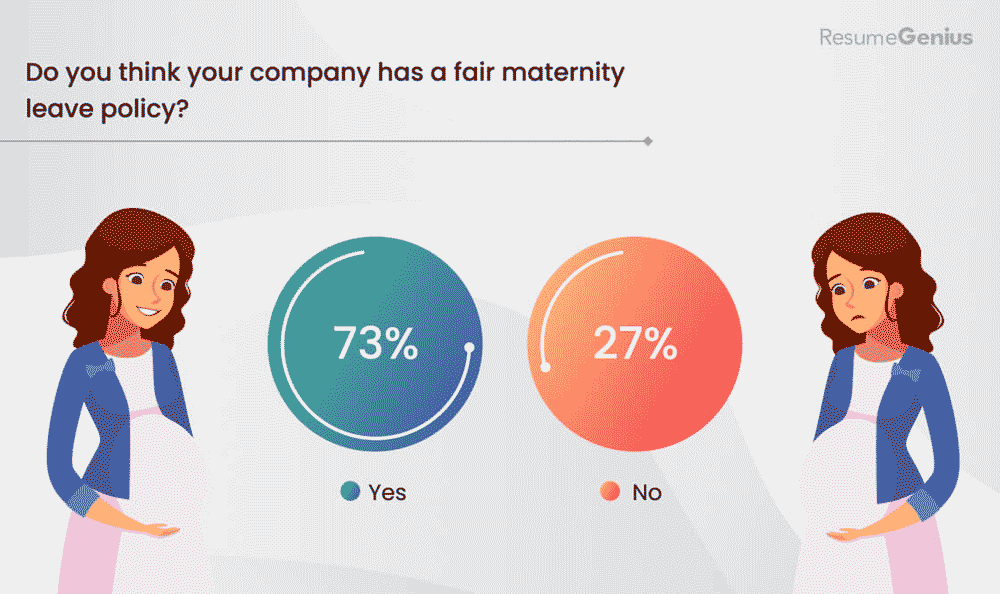

Overall though, across the US, 73% of people thought their company’s maternity leave policy was fair.

The data indicated that the vast majority of respondents were happy with the maternity leave policy offered by their company.

Views on the gender pay gap by region

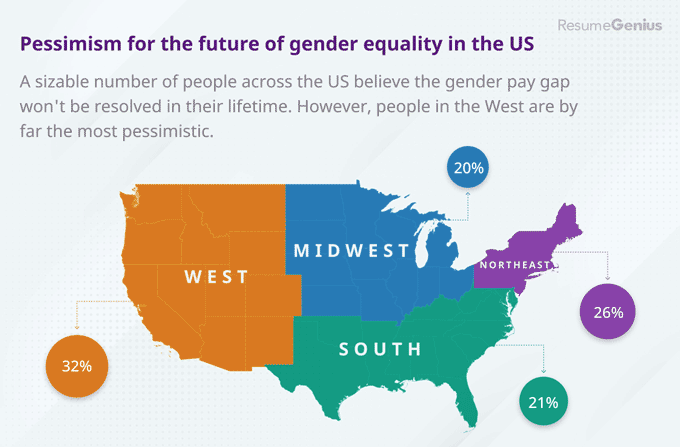

Survey respondents in the American West were most likely to have low hopes for the gender pay gap, despite the fact that some Western states have smaller pay gaps than elsewhere in the US:

In California US the state with the smallest gender pay gap, women make 88¢ for every $1 dollar a man makes. Meanwhile, Nevada has the 5th smallest gender pay gap, while Oregon has the 9th smallest.

The state with the biggest gender wage gap is Louisiana, where women make only 69¢ for every $1 a man makes.

Effect of discussing salary on the gender pay gap

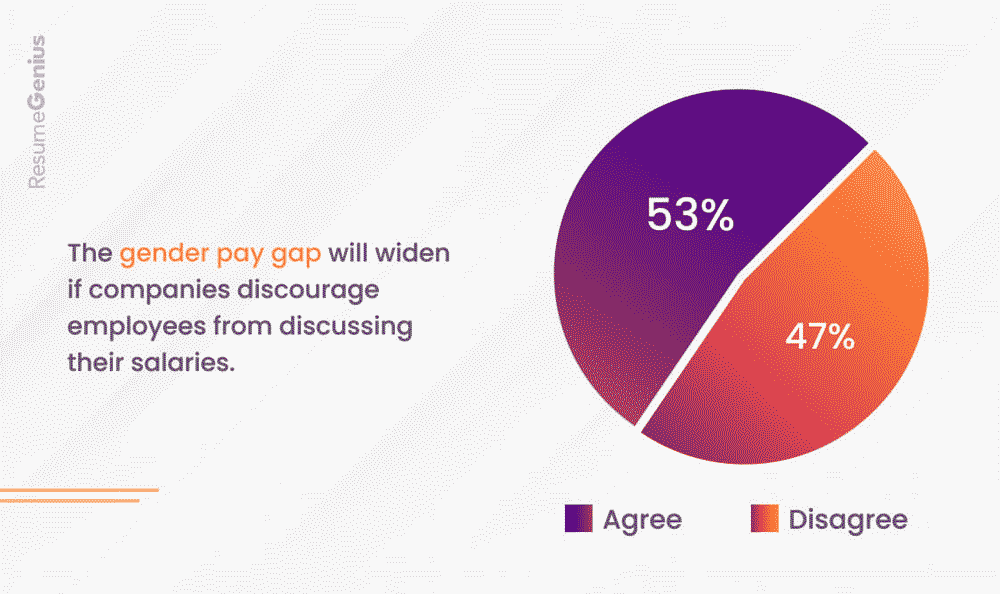

Our survey also offers insight into respondents’ views on the relationship between discussing salaries and the gender pay gap:

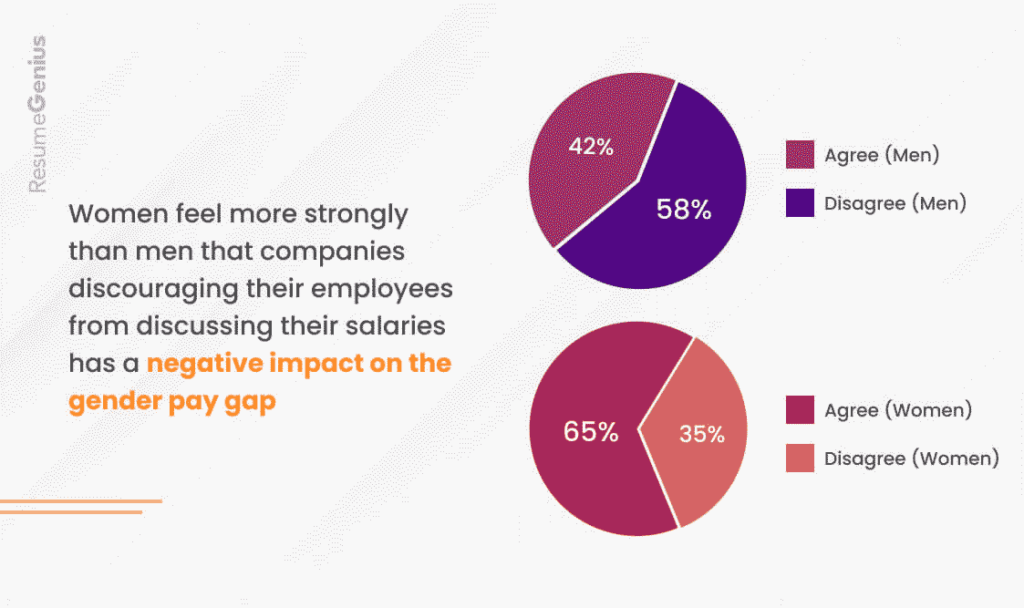

Women were more likely to believe that discouraging workers from discussing salaries would widen the gender pay gap:

How Americans feel about discussing their salaries with coworkers

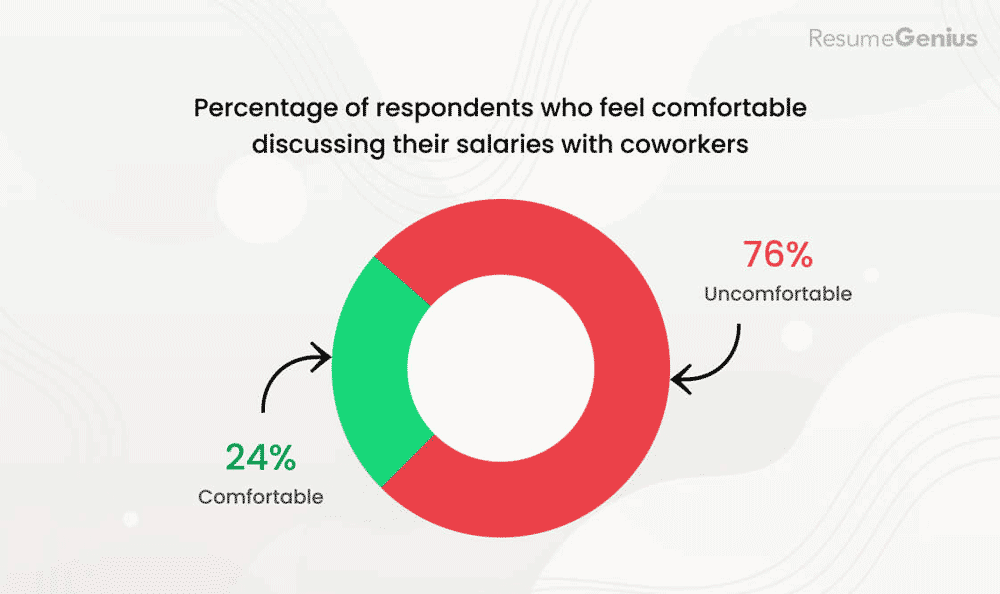

Most survey respondents said they don’t feel comfortable talking about how much they earn with their coworkers.

The majority (76%) stated that they’re uncomfortable discussing pay with coworkers:

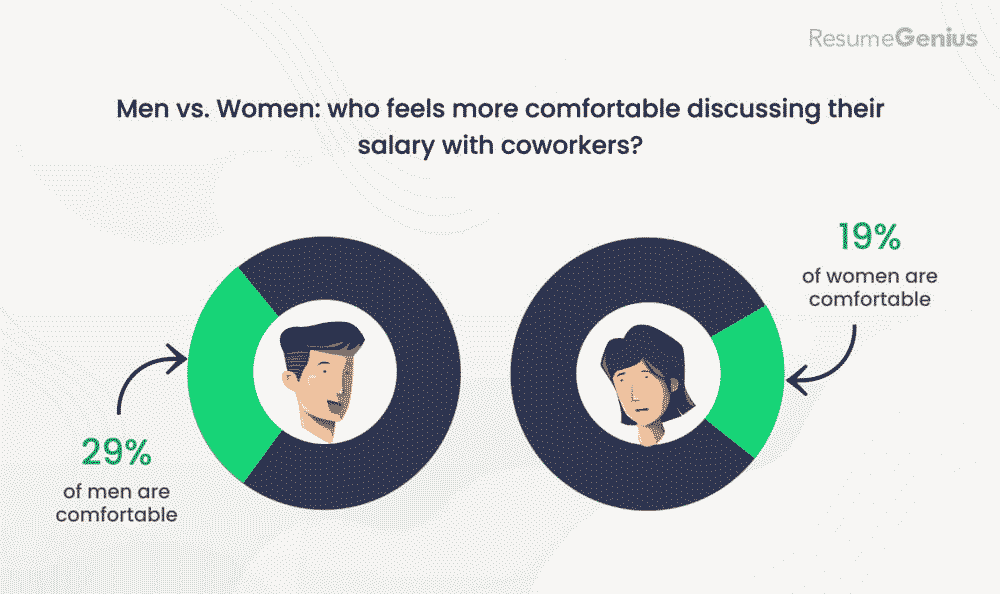

Women were more likely than men to feel uncomfortable about discussing their salary, with over 80% saying they felt this way:

How younger Americans feel about discussing their salaries

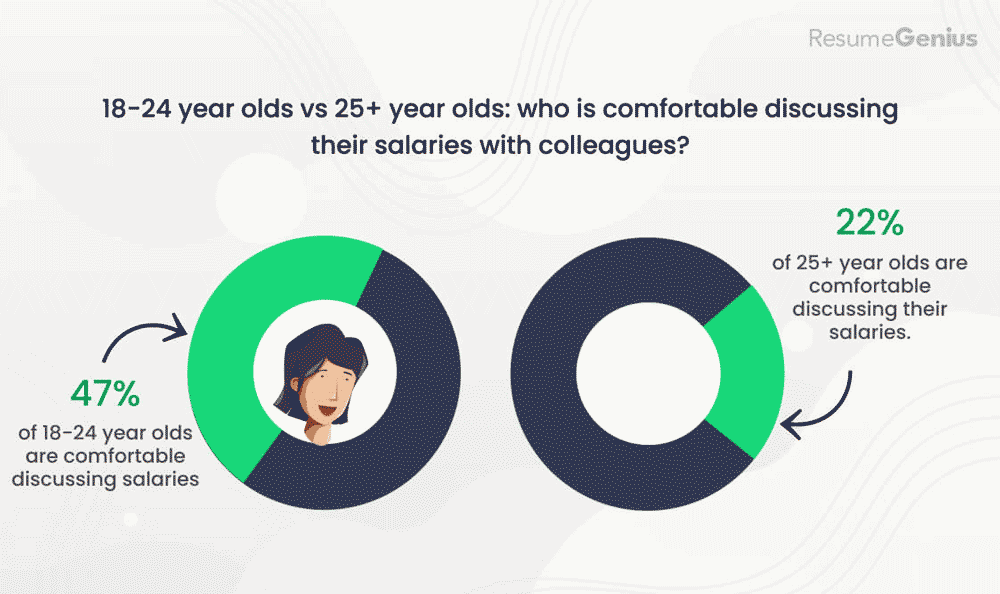

Younger workers were more likely to feel comfortable talking about their salaries.

Almost half of the people we surveyed aged 24 and under said they’d be happy to talk about their salary with their colleagues.

According to the Wall Street Journal, younger workers are more willing to talk about their salaries because of the challenges they’ve encountered entering the workforce in the aftermath of the 2008 recession, which include a lack of affordable housing and the rising cost of college education.

However, despite younger people being more willing to discuss their salary with their colleagues, the majority of respondents aged 18–24 years old said that discouraging employees from discussing salaries has no impact on the gender pay gap:

How people feel about asking for a raise

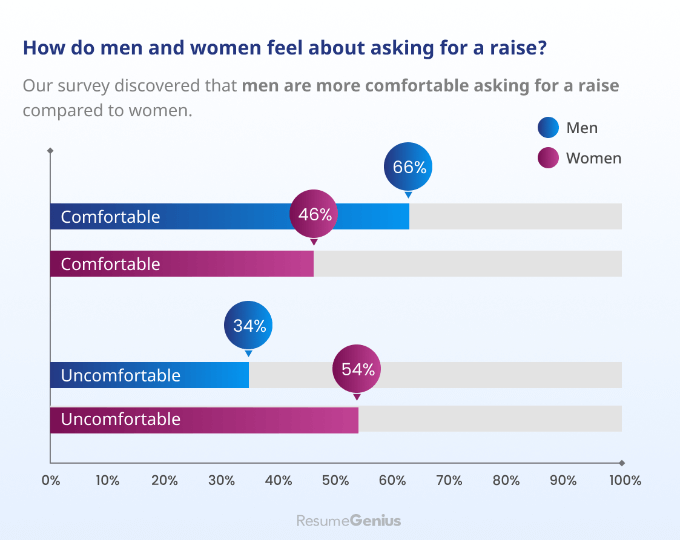

The data shows that most people asked were comfortable asking for a raise.

According to the survey, 56% of respondents said they were comfortable requesting a salary increase, while 44% said they would not feel comfortable doing so.

However, women were less likely than men to say they feel comfortable asking for raise:

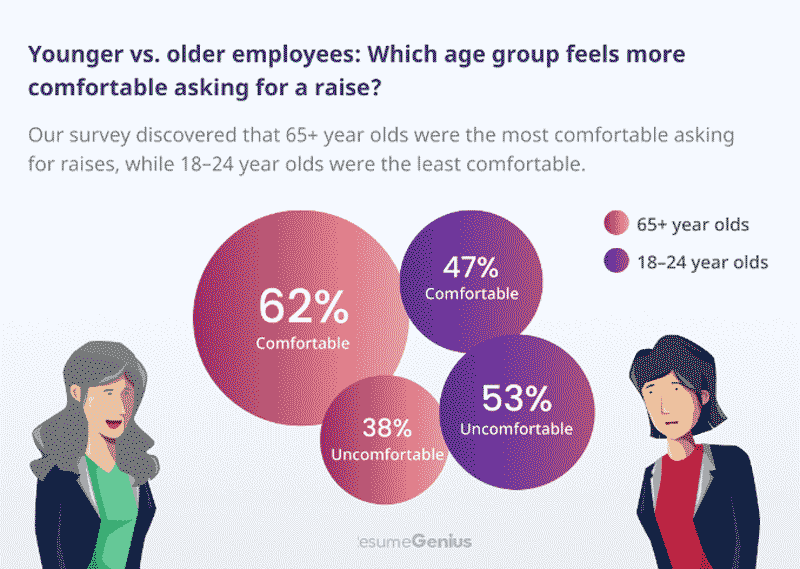

The data also suggests that younger people may be less willing to ask for a pay raise than older Americans are:

Effects of COVID-19 on the gender pay gap

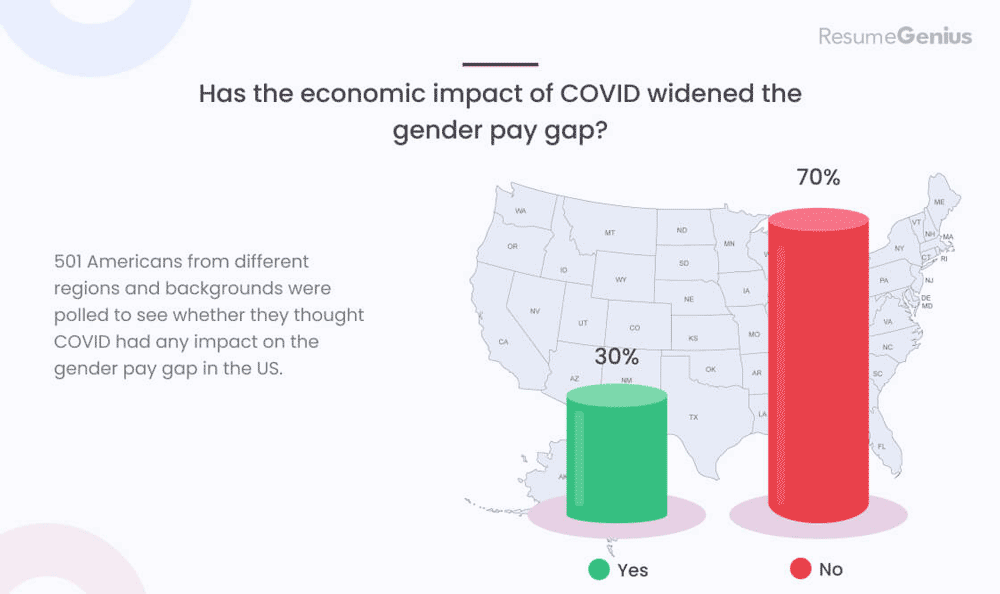

While most people agreed that being discouraged from discussing salaries sustains the gender pay gap, more than two-thirds of the people surveyed didn’t think that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a similar effect:

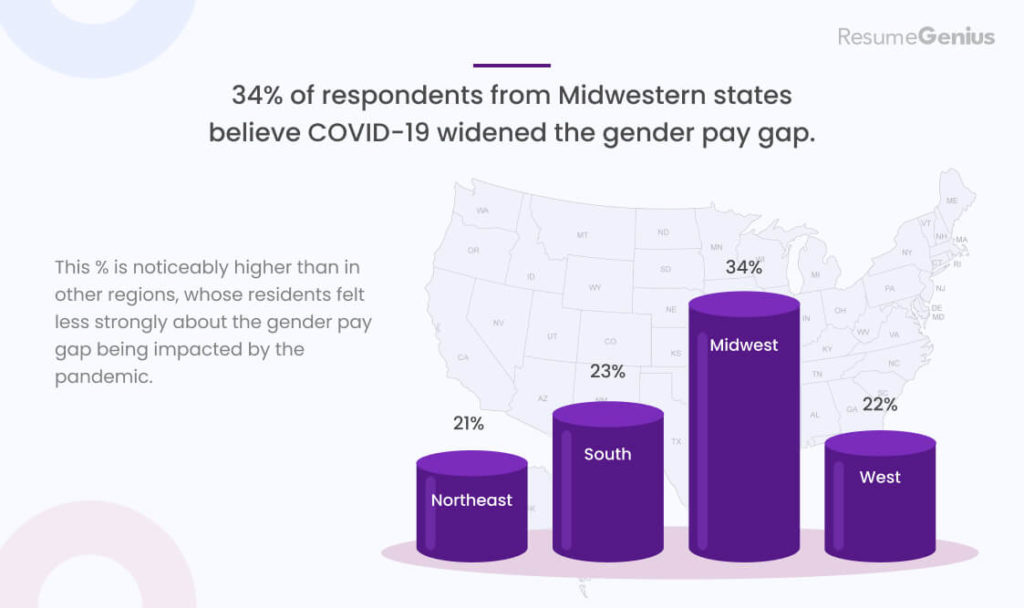

While most of the country felt the same, 34% of respondents from the Midwest stated they believed COVID-19 had widened the gender pay gap — the highest percentage of Americans who felt this way:

Attitudes toward the future of the gender pay gap

A quarter of workers aged between 35 and 45 were optimistic that the gender pay gap will disappear in their lifetimes in contrast to 7% of those aged 45 years or older:

Takeaways

If you want to help fight for gender pay equality, there are a few things you can do:

- Write to your representative and senators and ask them to prioritize gender pay equality

- Learn more from the National Committee on Pay Equity or the AAUW

- If you’re a working woman, consider joining a labor union and the Coalition of Labor Union Women

Build your resume in minutes

Use an AI-powered resume builder and have your resume done in 10 minutes. Just select your template and our software will guide you through the process.

About Resume Genius

Since 2009, Resume Genius has combined innovative technology with leading industry expertise to simplify the job hunt for people of all backgrounds and levels of experience.

Resume Genius’s easy-to-use resume builder and wide range of free career resources, including resume templates, cover letter samples, and resume writing guides, help job seekers find fulfilling work and reach their career goals. Resume Genius is led by a team of dedicated career advisors and HR experts and has been featured in The New York Times, Forbes, CNBC, and Business Insider.

For media inquiries, please contact us.